Even Lower-Skilled Natives Need Not Be Harmed by Immigration in the Labor Market

Oleg Firsin on the affect of offshoring on the wage impact of immigration

The question of how immigrants affect labor market outcomes of natives—mainly, employment and wages—has long been crucial to immigration policy debate.

The concern about negative repercussions from immigration for native workers was a significant part of the motivation for the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, for the termination of the Bracero Program in 1964, and for the more recent efforts to extend the wall along the US’s southern border. According to a recent Gallup Poll, about half of respondents think immigrants don’t impact job opportunities. Most of those who think they do, think the impact is negative.

This concern follows an intuitive logic and straightforward economic rationale that an increase in the supply of labor decreases its price (wage). This simple analysis has its place, but in immigration policy, it often misleads.

In a recent paper, I show that if natives concentrate on tasks where they have a productivity advantage (for example, those that heavily rely on communication skills), the effect of immigration—even on the most vulnerable natives—is minimized. Importantly, I show that the task concentration of natives is not static. In particular, offshoring changes the task distribution between natives and immigrants in a way that mutes the extent to which immigration negatively affects the wages of even the lowest-skilled natives. Concentrating on areas where natives have an advantage, like communication, can safeguard the wages of natives most at risk of negative wage effects.

I am not the first to show that the rationale from Econ 101, regarding the likely effects of an increased labor supply, is overly simplistic as a guide to immigration policy. Multiple economic studies over the years have found that natives as a whole do not suffer in the labor market from more immigration. Nor do they benefit from immigration restrictions. A recent meta-analysis of 64 papers published in scholarly journals finds “a negative and close to zero effect of immigration on native wages.”

Still, those in favor of more immigration restrictions would point out that the lack of an overall effect on all natives masks negative changes for certain groups of workers, especially the lower-skilled. The nuanced reality is that some natives lose while others benefit. The impact of immigration on native outcomes depends on the task distribution between natives and immigrants. A reasonable policy takeaway from my and others’ research is that, given the positive effects of immigration on some natives, minimizing the negative effects on others (through nudges to task specialization) may well turn the overall effect from negligible to robustly positive.

The near-zero overall effect of immigration masks positive and negative impacts

Immigration’s overall impact on the wages of all natives is negligible. However, looking at specific groups of natives reveals wage effects that are positive or zero on some groups and negative on others. For example, low-skilled workers concentrating on manual-intensive tasks can lose out while high-skilled workers in cognitive- or communication-intensive roles benefit.

Why does task specialization matter? And what determines the sorting between natives and immigrants?

Different types of workers do different types of work. They are not perfect substitutes. An American holding a PhD is not competing for jobs with immigrants who don’t, for example. Natives with the former level of educational attainment hardly compete with immigrants with the latter level. The question of the effect of low-skilled immigration on high-skilled natives is not a very controversial one. Little, if any, research suggests that low-skilled immigrants reduce the wages of high-skilled natives.

Even at similar skill levels, natives and immigrants specialize in different tasks

So how does immigration affect less-educated natives? Even among the low-skilled, natives and immigrants are not perfect substitutes and specialize in different tasks. This modifies the predicted wage effect. For example, an increase in the supply of immigrants performing more manual tasks may lead to an increase in the demand for supervisory workers who are more likely to be natives because natives have a comparative advantage in communication-intensive tasks (the ratio of native to immigrant productivity in such tasks is higher than in more manual tasks).

Wage effects depend on the balance between productivity and labor supply effects

An increase in immigrant labor pushes natives to concentrate on tasks in which they are more productive. This puts upward pressure on their wages. Economists call this the productivity effect. The competing effect of pushing wages downward is the labor supply effect.

Some tasks are interchangeable between low-skilled natives and immigrants. An increase in the number of low-skilled workers does put downward pressure on the average wages among all low-skilled workers.

The overall change in native wages depends on the balance between the productivity effect and the labor supply effect.

Wage effects are diminished if natives concentrate on tasks in which they are most productive

In my study, I show that if natives concentrate on tasks where they are most productive, their relative contribution to production grows, and that of immigrants diminishes. If immigrants contribute less to production, an increase in the number of immigrants will impact output and wages less than if they contribute more (this is generally true of any input in production). Among factors that can decrease the importance of immigrants in production (keeping the number of immigrants constant), I focus on one in particular—offshoring.

Offshoring can affect immigrant tasks and native tasks differently

Offshoring broadly means the relocation of some production tasks abroad. If those “offshored” tasks are tasks where immigrants are most productive relative to natives, then those left are tasks where they are less productive than natives. Do offshored tasks tend to be those where immigrants specialize? And is the sign of the wage effect of immigration that offshoring might reduce negatively or positively? These are empirical questions.

In the paper, I look at the effects of low-skilled foreign-born workers, focusing on those with at most high school education and those with some college. Consistent with the literature, I find that commuting zones (areas commonly taken to represent local labor markets) that experienced greater low-skilled immigration saw decreased wages of the low-skilled natives, but not high-skilled natives. This is a relatively small effect. Wages fell by 0.7% for each percentage point increase in the percentage of immigrants among the low-skilled.

Even low-skilled natives need not be harmed by immigration

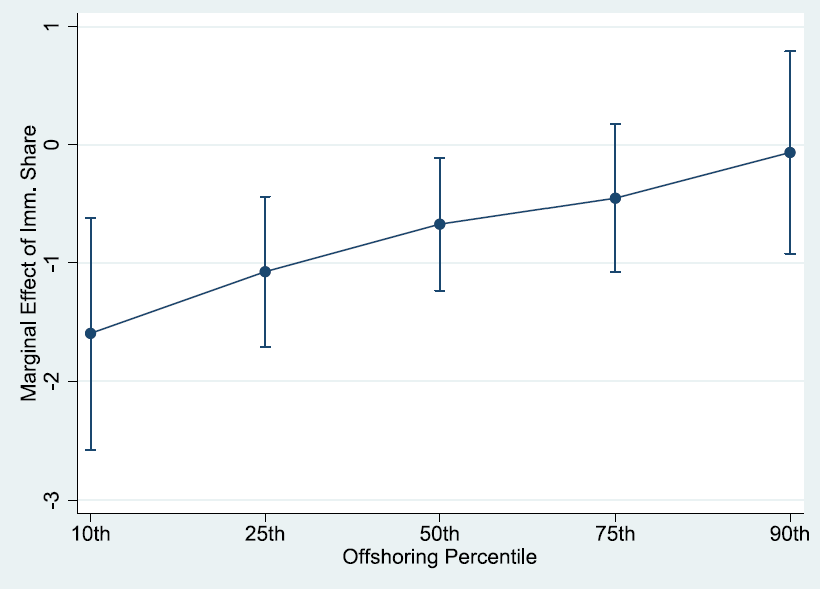

Not all natives seem to have to compete with immigrants. I find that the negative effect on the low-skilled natives tends to decrease as offshoring increases, eventually reaching a point where it is not statistically distinguishable from 0 in the highest offshoring quartile. This is illustrated in the figure below, in which the whiskers represent the bounds of the 95% confidence interval.

That this finding is consistent with the economic rationale outlined earlier is bolstered by the findings that a) natives concentrating in tasks they are less productive in magnifies the effect of immigration and b) offshoring is associated with natives concentrating in tasks they are more productive in (as evidenced by the share of overall labor payments they receive).

The takeaways go beyond offshoring

In sum, even workers within the same educational level are not homogenous and do not constitute perfect substitutes in production. Among the less-educated, natives and immigrants disproportionately sort into different occupations, which require different tasks and skills. Factors that can shift natives into tasks where they are most productive increase natives’ relative productivity and their wages. Because natives are now more important in production and immigrants less, their wages become less responsive to competition from immigration.

Offshoring is just one factor, but many factors can insulate natives from direct wage competition with immigrants. Certain types of automation, if they concentrate on tasks disproportionately done by immigrants, may also shift the task distribution in a way consistent with the main mechanism in the paper.

Among the factors more directly influenced by policy, managerial job training can help transition natives into supervisory roles more complementary to immigration. This is true for the high human capital industries, such as high-tech, as well as low human capital industries. To maximize the ability of American workers to work with immigrants in complementary roles, in many areas it would likely be beneficial to supplement the already present English language skills with job-related Spanish training. It is entirely plausible to turn the challenge of additional labor supply via immigration into an opportunity.

My research does not downplay that there are groups of American workers who see reduced wages in response to immigration. Instead, it suggests that there are feasible nudges to their task concentration that can diminish this effect—conceivably, to a statistically negligible magnitude. That is, policymakers can help natives adjust to a globalizing world. The best policy approach to protect natives is to focus on how to aid natives who feel left behind, not placing broad restrictions on immigration.

Oleg Firsin is the Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. His research focuses on international trade, labor economics, development economics, and applied macroeconomics.